Share This Article:

by Frank Sorochen, Esq., and Connor J. Thomson, CPCU, WRP

Roles of Workers’ Compensation Wholesale Brokers

Wholesale brokers are intermediaries between retail agents or brokers and insurance companies, facilitating access to markets, coverage, and reduced rates that are often unavailable through standard channels. Wholesale brokers are experts in niche lines of business (e.g., workers’ compensation), who service high-risk policyholders (e.g., artisan contractors).

In the workers’ compensation ecosystem, retail agents or brokers turn to wholesale brokers when a standard insurance company is unable or unwilling to underwrite a policy due to high claims frequency or severity, hazardous occupations or operational risks, state regulatory requirements, or fluctuating payrolls. Wholesale brokers can leverage their deep expertise and market clout to obtain coverage at a reduced rate. Wholesale brokers can also (1) offer unique coverage solutions (e.g., a “Small Business Owners Dividend Program” for certain hospitality, manufacturing, and professional service classes with premiums starting at $1,500, coupled with “Schedule Credits”); (2) advise on alternative risk transfer mechanisms (e.g., self-insurance programs with large deductible or retrospective rating plans); and (3) coordinate strategic loss control plans, effective return-to-work (i.e., modified duty) programs, and claim reviews. The intermediary nature of wholesale brokers truly “depopulates” the sales and servicing process for retail agents or brokers and simplifies the underwriting process for insurance companies.

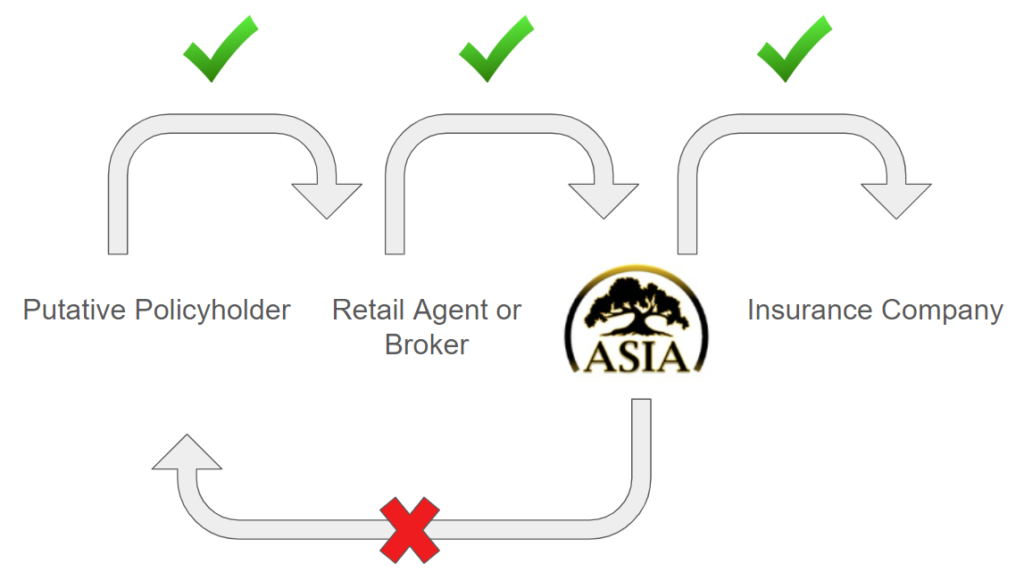

Pursuant to a federal court in the Northern District of Illinois, a wholesale broker has four distinct roles. See Brown & Brown, Inc. v. Muhammad Munawar Ali, 592 F. Supp. 2d 1009 (N.D. Ill. 2009). First, a wholesale broker receives a putative policyholder’s confidential information from a retail agent or broker. See id. at 1017 (noting that the wholesale broker does not maintain direct contact with the putative policyholder). The confidential information includes “the insurance services contemplated, policy term, target price, expiring price, expiring coverage, description of operations, loss history, and exposures.” Id. Second, the wholesale broker summarizes, assembles, and provides the confidential information to an insurance company based on its knowledge of the insurance company. See id. (suggesting that, because the insurance industry is “highly competitive and . . . relationship driven,” the more market clout the wholesale broker has, the more it can leverage its knowledge of the insurance company). Third, after the wholesale broker learns that the insurance company may be interested in insuring the putative policyholder, it analyzes the information returned by the insurance company and relays it to the retail agent or broker. See id. (noting, again, that the wholesale broker does not maintain direct contact with the putative policyholder). The information may be relayed via “a formal proposal[] or . . . bindable quote . . . , or it may simply be [relayed] over the phone or in an e-mail.” Id. Fourth, the wholesale broker may advocate on behalf of the putative policyholder, negotiating a rate reduction with the insurance company if the bindable quote is not competitive. See id. at 1023-24.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from the aforementioned case is that wholesale brokers do not maintain direct contact with putative policyholders. The question then becomes: how does maintaining bureaucratic distance affect the legal relationship between wholesale brokers and putative policyholders?

Legal Duties of Workers’ Compensation Wholesale Brokers

On April 11, 2002, an incident occurred at the Dragon Inn Restaurant in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where Asher Klein sustained an injury. See Raimo Corp. v. Indian Harbor Ins. Co., No. 611, 2005 Phila. Ct. Com. Pl. LEXIS 315, at *1 (Phila. Cnty. Ct. Com. Pl. July 15, 2005). The Restaurant was operated by Raimo Corporation and its sole shareholder, Isaac Leizerowski. See id.

Several months before Klein sustained his injury, Isaac Leizerowski sought to reduce the Restaurant’s rising insurance rates and asked his brother, Abraham Leizerowski, to secure a new quote. See id. at *2. Abraham Leizerowski contacted Herbert Rife of LS&L Incorporated to secure the new quote. See id.

On September 14, 2001, Rife informed Abraham Leizerowski that Indian Harbor Insurance Company would provide fire and liability coverage via Brokers Surplus, a wholesale broker. See id. It was not until Raimo and Isaac Leizerowski notified Rife, LS&L, and Indian Harbor of Klein’s incident on April 11, 2002, when they learned that no workers’ compensation coverage had been obtained. See id. at *3. Consequently, Raimo and Isaac Leizerowski filed a lawsuit against Brokers Surplus, alleging negligence for failure to obtain proper coverage. See id.

The primary element in a negligence claim is the defendant’s duty of care to the plaintiff. See Althaus v. Cohen, 756 A.2d 1166 (Pa. 2000). The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania identified several factors to determine whether a duty of care exists in a particular instance, such as the relationship between the parties, the social utility of the defendant’s conduct, the nature of the risk imposed and foreseeability of the harm incurred, the consequences of imposing a duty upon the defendant, and the overall public interest in the proposed solution. See id. at 1169. In a particular instance, a single factor may be determinative. See Atcovitz v. Gulph Mills Tennis Club, Inc., 812 A.2d 1218 (Pa. 2002).

Here, Raimo and Isaac Leizerowski used Abraham Leizerowski to secure the new quote, and Abraham Leizerowski communicated only with Rife, not Brokers Surplus. See Raimo Corp., 2005 Phila. Ct. Com. Pl. LEXIS 315, at *5. Deposition testimony confirmed that Brokers Surplus maintained no direct contact with Raimo and Isaac Leizerowski. See id. The lack of direct contact, coupled with Broker Surplus’s inability to see the alleged injury suffered by Raimo and Isaac Leizerowski, led to the conclusion that Broker Surplus did not owe a duty of care to Raimo and Isaac Leizerowski. See id. at *6.

The Reality

In conclusion, maintaining bureaucratic distance allows wholesale brokers to focus on their four distinct roles and do what they do best: facilitate access to markets, coverage, and reduced rates that are often unavailable through standard channels. However, the reality is that, once putative policyholders become actual policyholders, they call wholesale brokers with billing issues (i.e., ancillary and subsequent issues to the procurement and obtainment of coverage). Wholesale brokers are designated as the “Broker of Record” on Declaration pages, so actual policyholders view them as points of contact, who can assist with sales and servicing in a service-driven industry. It is important for wholesale brokers to maintain bureaucratic distance but distinguish between issues central versus ancillary and subsequent to the procurement and obtainment of coverage, striking a balance between mitigating legal liability and providing superb service.

For more information on this topic, please contact Frank Sorochen, Esq., at fsorochenjr@asiaworkerscomp.com or Connor J. Thomson, CPCU, WRP, at cthomso5@villanova.edu.

california case management case management focus claims compensability compliance courts covid do you know the rule emotions exclusive remedy florida FMLA fraud glossary check Healthcare health care hr homeroom insurance insurers iowa leadership medical NCCI new jersey new york ohio osha pennsylvania roadmap Safety state info technology texas violence WDYT west virginia what do you think women's history women's history month workcompcollege workers' comp 101 workers' recovery Workplace Safety Workplace Violence

Read Also

About The Author

About The Author

- Frank Sorochen Connor J. Thomson

Read More

- Apr 13, 2025

- Edward Stern

- Apr 08, 2025

- Frank Ferreri

- Apr 07, 2025

- Natalie Torres

- Apr 04, 2025

- Kristin Green

- Apr 03, 2025

- Shawn Deane

- Apr 01, 2025

- NCCI