Share This Article:

Los Angeles, CA (WorkersCompensation.com) – Four current and former Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department employees have died by suicide over a 24-hour span, officials said last week.

According to Los Angeles County Sheriff Robert Luna alluded to the stress officers have to go through and urged other law enforcement officers to reach out and check on their co-workers.

“We are stunned to learn of these deaths, and it has sent shock waves of emotions throughout the department as we try and cope with the loss of not just one, but four beloved active and retired members of our department family,” Luna said in an emailed statement Tuesday. “During trying times like these it’s important for personnel regardless of rank or position to check on the well-being of other colleagues and friends.”

Luna said he and his department were “exploring avenues to reduce work stress factors to support our employees’ work and personal lives.” The department is investigating the deaths.

Luna said one former and three current employees died by suicide within a 24-hour span on Monday. Among them was Cmdr. Darren Harris, found dead in his home in Santa Clarita on Monday morning. Sometime after noon, authorities found the body of Greg Hovland, a retired sergeant who worked in the Antelope Valley. Later, just after sunset, another employee was found dead just after sunset at their residence in Stevenson Ranch. The last death was reported at 7:30 a.m. on Tuesday, when detectives responded to a hospital in Pomona where an employee had died after committing suicide.

Another four officers have died by suicide in L.A.’s sheriff’s office, officials said.

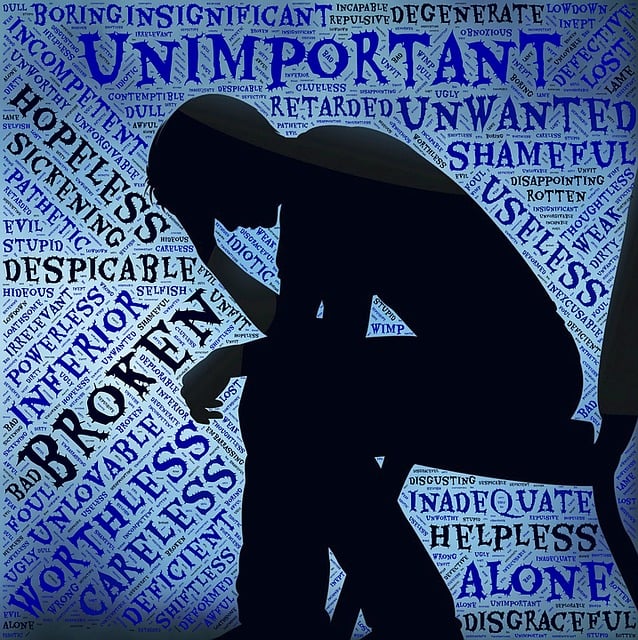

Police observers said the suicides underscore long-standing problems for law enforcement officers in Los Angeles, and across the country. Recent studies have shown that more officers have died by suicide than by being killed in the line of duty.

A study published by the National Institutes of Health found that retired officers were less likely to commit suicide than currently employed officers and that those at highest risk of suicide are those who have been working for between 15 and 20 years. Officers who have been working between 12 and 20 years have the highest stress rates, researchers found, and enter a “disenchantment” stage. Officers in that service range also have higher depression scores than their younger counterparts, the research found.

Officers are more likely to die by suicide than the general population, researchers have found, a fact attributed to higher stress rates caused by police work, and heightened scrutiny of police work in recent years, combined with officers access to firearms.

The risk of suicide is higher in smaller police departments, researchers said, many of which lack the mental health and counseling resources that could help officers who have suicidal thoughts.

According to Blue H.E.L.P, a website that track officer suicides, 81 officer have taken their lives this year across the country. Last year, the site said, more than 170 officers died by suicide. Since 2016, Blue H.E.L.P. has been compiling lists of law enforcement officers lost to suicide. In 2016, 152 officers died by suicide; in 2017, 176. After reaching a high of 236 in 2019, the number has been dropping.

Joe Willis, of First Help, the organization that encompasses Blue H.E.L.P, said departments have to provide resource for officers.

“It’s important for departments to provide mental health resources to their employees not just in the immediate aftermath of a tragedy, but well in advance,” he said in a statement on Facebook. “Though agencies may not always know how best to respond to suicide, not talking about it is not the right answer.”

Luna said his department’s Psychological Services Bureau and the Injury and Health Support Unit were working to give support, counseling and other services to the families of the officers who had taken their own lives.

“Additionally, the department has a Peer Support Program that members can use for additional assistance,” Luna said in his statement.

Willis said talking about what is available may not be enough.

“You’ve got to speak clearly about it, and you have to make resources available to the organization,” he said. “Leaders should be going to where their people are and having authentic, candid conversations with them about what is happening in the department.”

Willis said it was important for the officers to know themselves, to acknowledge their needs and to ask for and accept a helping hand when offered.

AI california case file caselaw case management case management focus claims compensability compliance compliance corner courts covid do you know the rule exclusive remedy florida glossary check Healthcare hr homeroom insurance insurers iowa kentucky leadership medical NCCI new jersey new york ohio pennsylvania roadmap Safety safety at work state info tech technology violence WDYT west virginia what do you think women's history women's history month workers' comp 101 workers' recovery Workplace Safety Workplace Violence

Read Also

- Dec 13, 2025

- Chris Parker

- Dec 12, 2025

- Chris Parker

About The Author

About The Author

-

Liz Carey

Liz Carey has worked as a writer, reporter and editor for nearly 25 years. First, as an investigative reporter for Gannett and later as the Vice President of a local Chamber of Commerce, Carey has covered everything from local government to the statehouse to the aerospace industry. Her work as a reporter, as well as her work in the community, have led her to become an advocate for the working poor, as well as the small business owner.

Read More

- Dec 13, 2025

- Chris Parker

- Dec 12, 2025

- Chris Parker

- Dec 11, 2025

- Chriss Swaney

- Dec 11, 2025

- Liz Carey

- Dec 11, 2025

- Frank Ferreri

- Dec 10, 2025

- Liz Carey