The concept of electronic filing was conceptualized early in the 21st century and eventually deployed in 2005. I never imagined or envisioned where we are today, but was an early adopter of accepting emailed PDF files early this century. As the system (e-JCC) was born, I quickly became a fan and enthusiast. The FloridOJCC led the e-filing revolution and we are proud of that. The development and evolution of that process have been aptly documented and does not be repeating here.

Suffice it to say, that the process has saved lawyers, parties, and the state millions of dollars. Those are hard savings in paper, postage, and more. There have been greater savings in efficiency, saved time, etc. It has been nothing short of revolutionary. Practitioners will know that in that process, in the evolution since its inception, the OJCC also began generating orders at its district offices.

The procedural process of Worker’s Compensation litigation in Florida was materially and coincidentally altered by the supreme court‘s admission in 2004 that it lacked authority to enact procedural rules for this office. The legislature had long before statutorily shifted rulemaking authority to the Office of Judges of Compensation Claims and then the Division of Administrative Hearings. Shifted, because the Legislature had initially acquiesced in the Supreme Court's 1973 usurpation of authority in adopting OJCC procedural rules.

Notably, the adoption of rules by DOAH in the twenty-first century led to litigation. Many lawyers were convinced that the legislature, and it's directing the adoption of administrative rules, was instead somehow usurping the authority of the courts. An entire generation had practiced a career under those Court rules, over about 30 years. The Supreme Court involvement in this administrative agency was familiar, comfortable, and habit to them. But, it was wrong. Seeing lawyers that could (would) not understand that was troubling. It was an interesting time to live and grow.

With the adoption of administrative rules, came the broad prescription of the submission of proposed orders. Proposed orders were once the norm, and were expected with motions. The Administrative rule vision encompassed, instead, the production of orders by judges. To some that was a novel concept, even perhaps radical. Imagine, judges producing orders? To some lawyers, it remains a novel concept today.

Despite the procedural rules clearly and succinctly instructing not to submit proposed orders, the practice persists with some attorneys. Rule 60Q6.103(4)("proposed orders shall not be submitted unless requested by the judge"). There is seemingly no question regarding the meaning of "shall not," nor "proposed orders." I ask judges periodically why they perceive lawyers still doing so, in violation of this rule, and the response is usually "habit, I suspect."

This proposed order habit or artifact from yesteryear periodically comes to my attention, as it did recently. A judge executed an order submitted by the parties, and the order did not include a certificate of service. That rare instance in which untoward behavior (submitting proposed orders) is met with acquiescence (using proposed orders) perhaps encourages the rule violators in their persistence?

In reviewing the missing certificate of service matter in this instance, it soon struck me that half of the first page of that order was consumed by a style that listed the names, addresses, and more of all parties. I have seen examples in which the entire first page consists of such surplusage. You would literally have to proceed to page two even see the title of the motion. I considered publishing an image of one of those for clarity but decided to avoid embarrassing anyone for either their antiquated surplusage habit or rule violation.

I did check my surroundings for signs of Marty McFly (Back to the Future, Universal, 1985). None were found. I was, nevertheless, feeling as if I’d been pulled into a time warp as I viewed that long page of names, addresses, and phone numbers. My fellow old–timers will remember that such a case style was once normal, “back in the day." That is, in the 20th century. However, great portions of our 20th-century efforts have yielded to modernization, streamlining, and efficiency. Gone are "open motion calendars," "joint petition days," color-coded orders, and various other eccentricities and inefficiencies. The rules changed. Technology changed. And in the end, we changed (well most of us). Why has your practice and case style not?

Most of us changed. But some still fill vast spaces with anachronistic case styles loaded with redundancy and superfluity. What could be simple one-page order with a normal, modern case style is easily two pages due to this senseless homage to yesteryear. It is more frustrating when the lawyer has so assiduously prepared such a style and then omitted the certificate of service. Certainly, with electronic service, the listing of recipients is of less necessity. But, in this instance, the order was on withdrawal of counsel. We will always wonder if the Claimant was served with that order as there is no electronic service record, and the order is silent, deficient, and lamentable. Is the mistake on that certificate issue:

- the lawyer's for submitting a proposed order?

- the lawyer's for not including the certificate in that proposed order?

- The judge's for not preparing her/his own order?

- Answer "D" was always troublesome "all of the above?"

In preparing this post, I wondered how many gigabytes of memory is being consumed by the volume of proposed orders submitted in violation of the procedural rules. Each day, our database of filings grows. It is inexorable, persistent, and cumulative. It is amazing that the Rules literally say "shall not" and yet lawyers still do. That these orders include the 1990s antiquated case style and its wasted space merely consumes space in the database.

I also wondered how much attorney and paralegal time is consumed each day in preparing such proposed orders. And I wondered why such effort is persistently invested in these large, unnecessary, and antiquated case styles. Is it because of habit? ("we've always done it this way."). Are those data points already lodged in the attorney's data system and the antiquated forms are too numerous to adjust and modernize? Is it just easier to continue to produce without ever considering a better, more efficient, process? See

The 5 Monkey Parable (February 2021).

If the issue is that an attorney's forms include this massive case style, and it would take time to modernize and rectify, why not fix one form at a time? Perhaps one might use "copy and paste" in a process where the style is fixed but once, and then pasted into other forms? Abraham Lincoln is credited with saying "if I had only one hour to chop down a tree, I would spend the first 45 minutes sharpening my axe." Getting the tools right, though it would take some time, would make the work thereafter more efficient and productive.

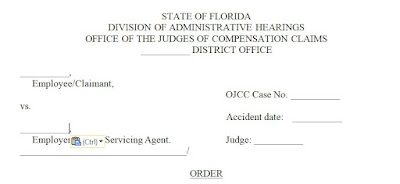

In the end, why so many words? Why are there filings with these large case styles that persist as we near the second decade of Administrative Rules in Chapter 60Q? They serve no purpose and they waste space. Save the time used building those old, clunky case styles. Save the space to store them. The case style should be simple, like this:

Anything more is a waste of our space, precious bandwidth, and your time. There is no reason for more. There is no reason at all for proposed orders "unless requested by the judge." Save the time of creating them. Save the space of storing them.

By Judge David Langham

Courtesy of Florida Workers' Comp